Did you watch the recent BBC drama, The Pale Horse? It is an adaptation of Agatha Christie’s 1961 murder mystery in which a dying woman leaves a list of names of people who die in unexplained circumstances.

The drama centres around three ‘witches’ in the village of Much Deeping (below right) , who tell fortunes and (at least in the mind of one of the characters) place curses on victims, causing them to die.

The idea of having one’s fortune told has a very (very) long history. From ancient times those with the gift of prophesy or ‘sight’ have been sought out by kings and chieftains, and those who just want to know who and when they’ll marry.

Until the eighteenth century those deemed to be practicing witchcraft could hanged if convicted and although the laws against witchcraft were repealed in 1736 so-called witches were still targeted well into the 1800s. The 1735 Witchcraft Act had effectively abolished the crime of witchcraft but made it illegal to claim magical powers. This continued to be used against those who said they could ‘summons spirits’, as both Helen Duncan and Jane Yorke discovered in 1944 when they were last two people to be prosecuted under the act.

According to the Police Code Book of 1889 fortune telling was also prohibited. The section reads:

‘Every person pretending of professing to tell fortunes, or using any subtle craft, means, or device, by palmistry or otherwise, to deceive and impose on any one, may be treated as a rogue and vagabond, and sentenced to imprisonment with hard labour’.1

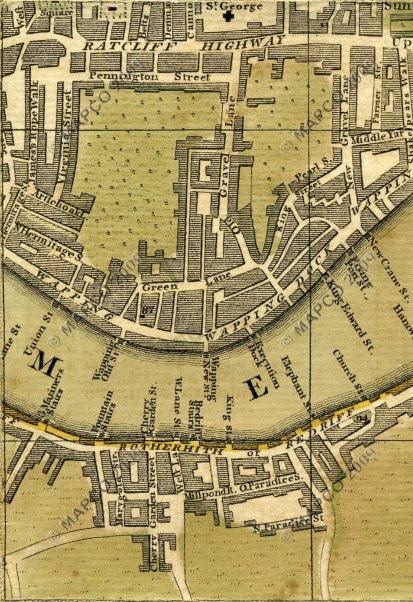

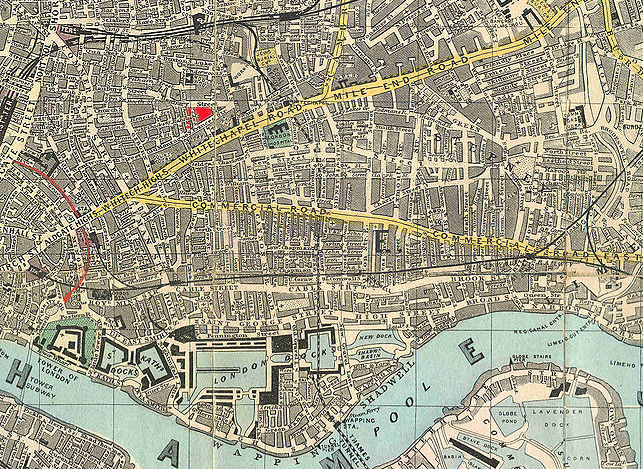

This offence fell under the ‘catch all’ terms of the Vagrancy Act (1824) and in February 1884 it ensnared an elderly woman called Antonia Spike. Spike appeared before Mr Lushington at Thames Police court. She’d been brought in on a warrant by sergeant White of H Division who’d been watching her for weeks.

White testified in court that he’d often seen women going coming and going at the house where Spike lived, sometimes as many as 8 or 9 in a single day. On the 18 February Eliza Weedon (a tenant on Whitechapel High Street) and Annie Wheeler, who lived in Shadwell, were among Spike’s visitors. Somehow the police sergeant persuaded them to give evidence before the magistrate.

They said that they had entered the house and Antonia Spike asked them if they wished to have their fortunes told. They said they did and Spike proceeded to shuffle and a pack of cards before giving them to Wheeler to cut

‘Are you married?’ she asked Annie, who said she was.

‘You will have a letter from a fair man, with a present, and you will be pleased. You will hear of the death of a dark woman, and you will come into some money. You will cross the ocean, and be married a second time, and be very well off’.

She also read Eliza’s fortune but presumably that was less interesting so the reporter didn’t write it down. Both women paid Antonia sixpence for reading their futures.

Mr Lushington, not a man to suffer fools or charlatans easily, sent the old lady to prison for a month with hard labour.

I had my fortune read once, in Aylesbury by a man who described himself as a warlock. He used the tarot and had an impressive statue of Anubis over his front door. He said I’d travel overseas, and that someone close to me, and elderly, would die. I paid more than 6d.

[from The Standard, Monday 25 February, 1884]

- From Sir Howard Vincent’s Police Code 1889, (ed by Neil. A Bell and Adam Wood, Mango Books, 2015), p.88